Venice, 28 November 2022 - Seducing while concealing unpleasant odour. To do so, they used to smell wigs, clothes, gloves, body, fans, coins and the environments in which they lived. The musketeers were the holders of these secret recipes, which mixed rose, lavender, orange blossom, musk, ambergris and civet for which they were paid “handsomely” representing the privileged status and flourishing trade of Venice. The perfumer was the “muschiere”, whose name comes from the word musk, originally called moscado, a very expensive secretion produced by a hairy bag placed near the navel of the cervid that lives in the mountains of the central and eastern Asia. The musk was not only used in the art of perfumery but also as a therapeutic substance and as an ingredient to embalm dead bodies. Substances of animal origin were the most used between the late Middle Ages and the beginning of the Modern Age, at a time when smells had to be strong to conceal poor hygiene conditions.

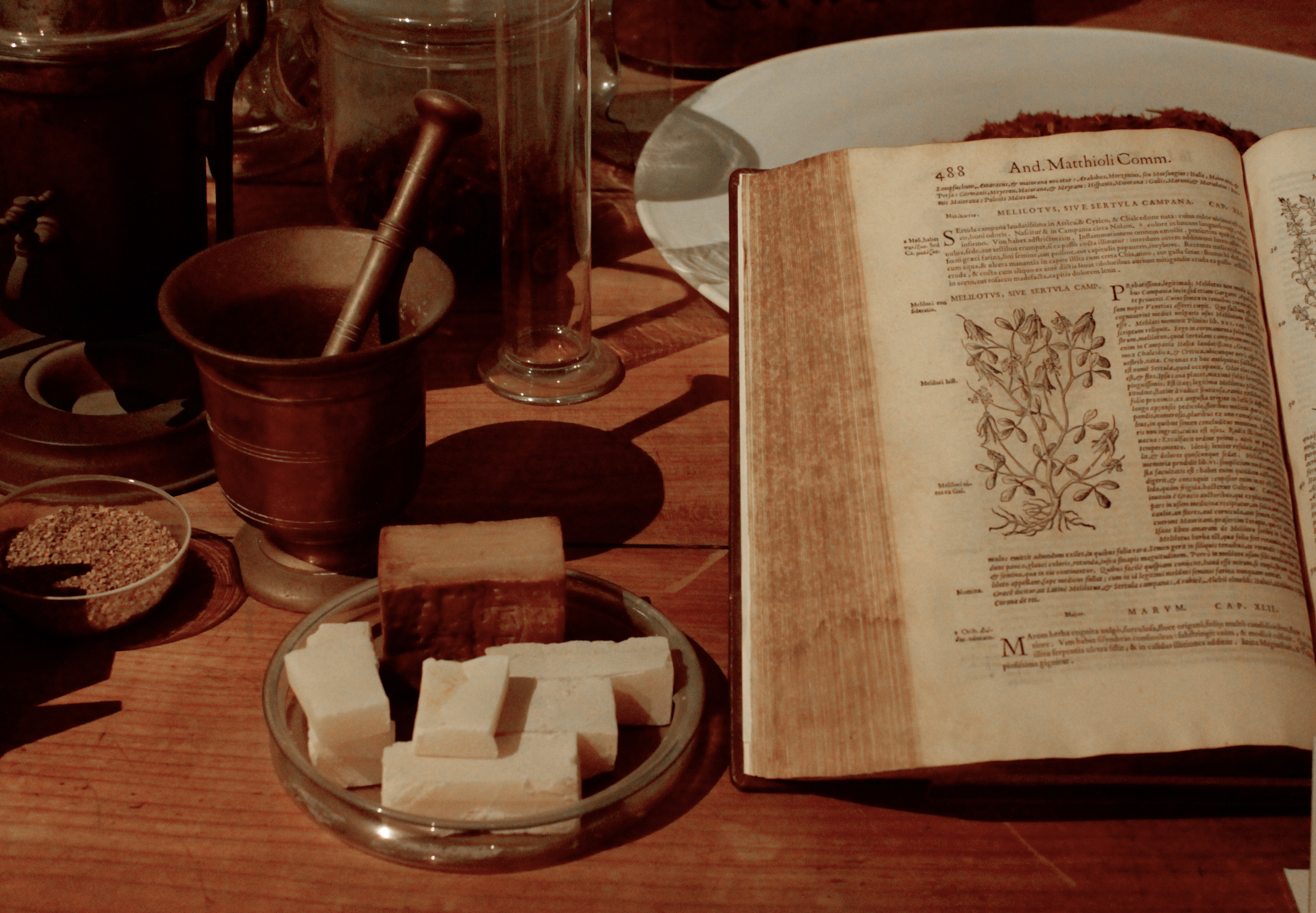

The hands and skills of these alchemists created a mixture that conquered the courts of Europe. The scents of the Serenissima's muschieri combined the oily balms of the East with alcoholic substances and fragrant essences. They used to dilute the essences with brandy rather than oil, a revolutionary technique that allowed them to store and market perfumes as never before. The musketeers kept fragrances in small luxurious handmade glass bottles produced by Murano glassmakers. This choice made them available to all rules and nobles, men and women, reachable by sea from the Serenissima.

In 1568 the shops of the muschieri were 24. Around the area of Rialto bridge there were six shops an many more along the route of the Mercerie, up to Piazza San Marco. The shops had very peculiar names, such as “Al Goglio”, “Alla Fenice”, “Alla Fortuna”, “Al Gatto”, “Alla Ninfa”, “Alla Pigna”, “Alla Sirena”, “Al Serpente”, “Ai Tre Calici”, and there they used to sell musk, amber, waters, oils, scented pasta, civet, ambergris, Cyprus powder and scented leather gloves. The muschieri not only created perfumed waters but also scented pastes, beauty creams and hair dyes to satisfy the vanity of the Venetian noblewomen.

In 1574, Henry III, King of France, on a visit to Venice, entered the workshop of the perfumer Domenico Ventura, who had his workshop in Merceria under the banner of Giglio, and allowed himself very expensive purchases: he bought moss for 1,125 scudi, a dizzying figure. At that time, Ventura was a muschiere famous for selling “rare things in the world” and serving most of the sovereigns and princes of Europe.

In 1660 the muschieri were 29 and, according to the documents, it is known that 81 people were employed among workers and apprentices. Among them there were also women who might have inherited the workshops from their deceased husbands and continued their activity. Nevertheless, there were also shops in Ruga degli Oresi, Santa Maria Formosa, San Pantalon and San Giovanni Grisostomo.

In the 18th century the shops were about thirty and continued to be located within the area of San Marco, especially in the parishes of San Zulian, San Bartolomeo and San Moisè and in the neighbouring areas such as Santa Maria Formosa and Santi Apostoli.

This profession was in the hands, by a large majority, of perfumers born in Venice, where families have been passed on the handcraft expertise since genereations.

When Napoleon came, the supremacy of Venice in the art of perfume cesead, with a shift from workshops to factories.